Eventually Gen-X took the vibes of punk and funk and made them into mini-fashion trends

They were the latchkey kids who figured out how to microwave TV dinners while watching MTV in empty houses. That was where they got their fashion education—absorbing Madonna's cone bras and Prince's ruffled shirts through cathode-ray filters. While this sect of Boomers epidemically passed time comparing muscle cars outside their local mini-marts, like a scene straight out of Dazed & Confused, Gen-X quietly absorbed every cultural signal available through coaxial cable wires, like IV drips of awesome.

Gen-X aesthetic sensibility emerged not from interning at fashion's ivory towers of the time. It hatched in basement-level record stores, at shows where headlining bands performed to audiences whose thrifted flannel told more authentic stories than designer lookbooks. The movements that emerged weren't calculated trend forecasts; they were spontaneous chemical reactions between boredom, cynicism, and desperate needs to differentiate from both hippies and Alex P. Keatons surrounding them.

These sibling movements—Sophistipunk and Sophistifunk—represent Gen-X's most authentic fashion contribution: taking established cultural codes and rewriting them with equal parts reverence and rebellion. They're worth examining not just as historical curiosities, but as blueprints for how genuine style evolution happens—not in boardrooms or on runways, but in the creative collisions of real life.

History Was Made In Plain Sight

The youngest of the Boomers and the eldest of Gen-X started two slept-on fashion movements that won't be taught in fashion design school. The first was spawned by the children of counter-culturists and happened between Michael Douglas's respective roles on Streets of San Francisco (that 70s cop show) and Wall Street (the quintessential 80s corporate greed flick). The first character: a young hotshot detective in the Harvey Milk S.F. era, who goes skiing and drives a Porsche 911. The second character: a Wall Street rainmaker during NYC's ruled-by-yuppies era of excess, who equates the Porsche 911 to a modern-day Toyota Prius.

Nah-theless (English language contribution #2), this isn't about Steve Keller and Gordon Gekko, this is about what happened in plain sight between dressing with flower-powered bell-bottoms, and sporting white lapels no matter the shirt color, and power suits that were powered by shoulder pads that were ear-level in height.

These movements happened in cultural shadowlands, in that space between "I want my MTV" and "Just Say No." Sophistipunk and Sophistifunk weren't documented in Women's Wear Daily or Vogue—they lived in corners of Tower Records, in back rows of movie theaters showing The Breakfast Club for the fifth time, in dorm rooms where debates raged over whether The Cure or New Order was more authentic.

The truth about fashion history: it's written by winners, and winners usually wear Chanel. But the real story? The real story happened in thrift stores where kids found old blazers and stuck safety pins through lapels because irony was their favorite accessory. The real story happened when they took their parents' Brooks Brothers leftovers and paired them with combat boots because contradiction was their brand. And yes, this writer claims to have also invented the labels of Sophistipunk and Sophistifunk (4 total linguistic contributions).

Sophistipunk: From Street to Mall and Back Again

First, let's break down Sophistipunk's dual life in the 80s:

The Mall Version

Picture this: Speed-walking past Spencer's Gifts, past that weird store that only sold unicorn merchandise and gag gifts for Dad, straight to Merry-Go-Round, which must've been a front since no one ever bought anything there. At the same time in movie theaters, Mannequin was somehow convincing America that Kim Cattrall could believably play a department store dummy. Those who were around back then may or may not have realized suburban Sophistipunk was having its moment.

Picture it: The Brat Pack was living their mall years, during that weird time between teen idol status and St. Elmo's Fire. Pre-serious acting careers, post-John Hughes golden age of Chicago youth dramedies. The Pack basically became Sophistipunk mascots: wearing designer labels with just enough edge to seem rebellious to parents of the time, but not enough to get their kids grounded from talking on the landline after dinner.

The mall version of Sophistipunk was like diet soda of rebellion—all attitude, no calories. Chess King sold "punk" blazers with attached safety pins, missing the point so hard it became performance art. Food courts became runways, where kids strutted past Orange Julius in asymmetrical haircuts and acid-washed attempts at edginess, knowing deep down they were cosplaying at rebellion.

Remember Delia's catalog? That was Sophistipunk's suburban safe word. Rebellion could be ordered by the mailbox-full, delivered discreetly to cul-de-sacs. Models wore Doc Martens with Laura Ashley dresses, creating sanitized versions of refinement-meets-raw that actual Sophistipunk embodied. It resembled watching parents attempt moonwalks—technically correct but spiritually vacant.

Meanwhile in Chicago, John Hughes accidentally created Sophistipunk's visual manifesto. Duckie wasn't just a character—he became a prophet in thrift store blazers. Rich kids in pastel polos were thesis; burnouts in army jackets were antithesis; and Duckie, in vintage jackets adorned with buttons and brooches, was synthesis. Pure Sophistipunk: smart enough to know better, punk enough not to care.

The Real Deal

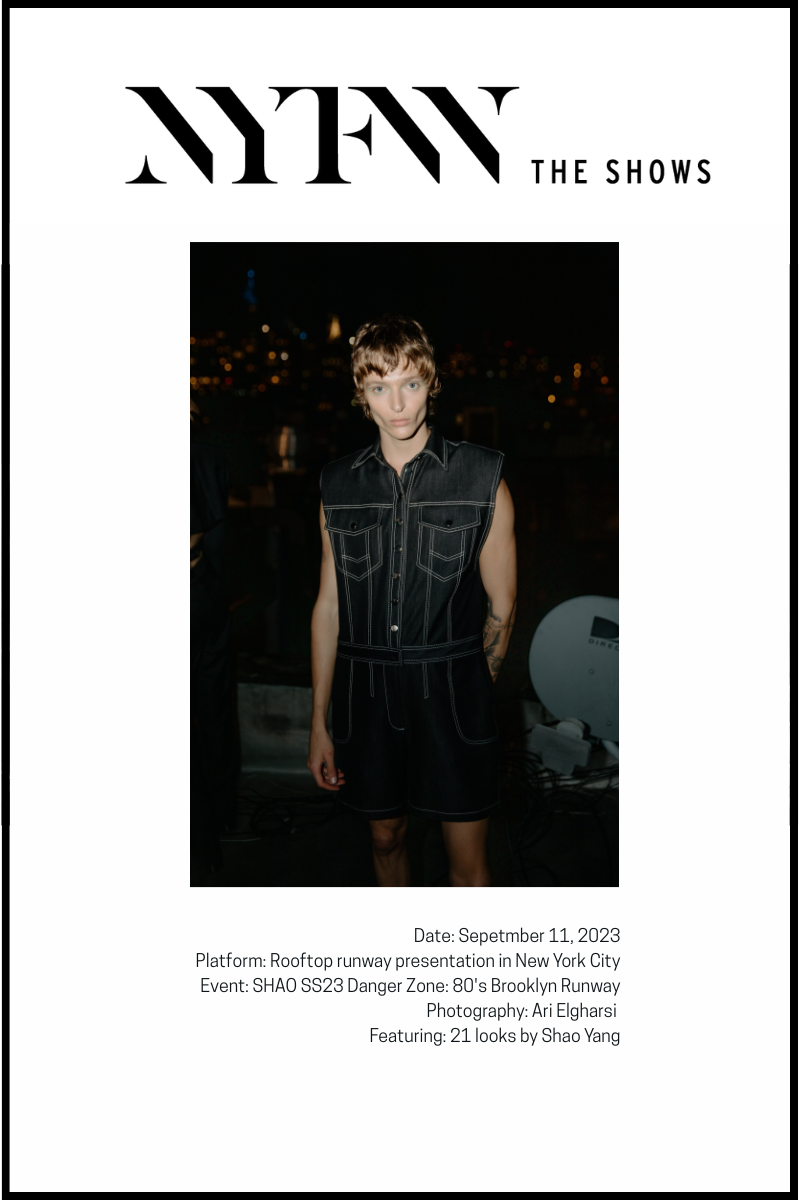

But while suburban kids were playing dress-up, NYC was developing something realer. As SHAO's Head Designer witnessed firsthand after moving from Taiwan to Bensonhurst: "That dark street chic look was everywhere." This wasn't mall punk - this was MTV coming of age, the Beastie Boys embodying Brooklyn's edge, Billy Idol writing about Richard Hambleton's ShadowMan (those mysterious black silhouettes painted on buildings) haunting the East Village.

The street version of Sophistipunk had teeth.

When Billy Idol wrote (Do Not) Stand in the Shadows, he wasn't just dropping a track - he was documenting how Hambleton's shadow figures were turning the Village into an outdoor gallery/haunted house.

The Beastie Boys weren't just punk kids gone hip-hop; they were the living embodiment of how NYC was mashing up everything cool and making it cooler.

The NYC Sophistipunk witnessed by SHAO's Head Designer marked real evolutionary leaps. This wasn't about mixing punk and preppy at The Limited. This represented survival aesthetics—when cities became barely contained disasters, clothes transformed into armor. Sophistipunk emerging from East Village wasn't trying to look dangerous; it acknowledged that danger was ambient temperature of daily life.

Keith Haring turned subway stations into galleries, and kids took note. They'd pair grandfather's old suit jackets with ripped jeans not for aesthetics, but because jackets were free and jeans had lived through actual life. CBGB's bathroom graffiti (that iconic punk club where artistic revolution happened in between sets) held more artistic integrity than half the galleries uptown, and Sophistipunk was there taking notes in margins.

The Mudd Club (that legendary downtown NYC venue where art, punk, and fashion collided) became Sophistipunk's laboratory, where artists, musicians, and Wall Street refugees mixed in spaces smelling of possibility and spilled beer. Brokers still in ties danced next to punks in full regalia, both equally lost and found. This wasn't fashion as costume—it was fashion as documentary.

While Sophistipunk was rewriting fashion rules on the East Coast through cultural collision and urban necessity, something equally revolutionary but distinctively different was emerging on the opposite shore. Both movements shared Gen-X DNA—that ability to simultaneously embrace and subvert tradition—but expressed it through entirely different cultural vocabularies.

Sophistifunk: From P-Funk to G-Funk

While Sophistipunk became New York's primal scream in polyester and safety pins, Sophistifunk gestated on opposite coasts.

Gen-X inherited P-Funk legacy (Parliament-Funkadelic's cosmic afrofuturism) like trust funds they didn't request but knew exactly how to spend. George Clinton laid foundations with cosmic runway shows masquerading as concerts. But Gen-X was about to renovate those motherships into something entirely their own.

Transitions from P-Funk to G-Funk (that West Coast hip-hop sound that defined the 90s) weren't just musical—they were sartorial alchemy. Purple velvet and platform boots of predecessors filtered through harsh California sun until emerging as something entirely new. Sophistifunk revival wasn't nostalgia; it was evolution with bouncing baselines.

The GenX revival of Sophistifunk happened when West Coast G-Funk went viral. This wasn't just about Parliament-Funkadelic anymore (though respect to the originators). This was post-NWA breakup, when everything changed.

West Coast G-Funk – short for gangsta funk—emerged as hip-hop's most stylistically influential sub-genre in the early 90s. More than just music, it was a complete cultural aesthetic. Those heavy synthesizers and slowed-down tempos sampling P-Funk weren't just sound – they were a vibe that translated directly into fashion statements.

Ice Cube emerged as one of Sophistifunk's most influential style architects. From his NWA days in all-black Raiders gear to his solo evolution, Cube perfected that precise balance of intimidating and immaculate. In Boyz N The Hood, his Doughboy character's wardrobe of crisp white tees, perfectly creased khakis, and gold chains—became as influential as any runway collection that year. Cube's style philosophy was clear: street authenticity didn't mean sacrificing precision.

Let's not forget Eazy-E, whose visual signature—that soul glow jheri curl peeking from beneath his Compton cap – created an instantly recognizable silhouette. Eazy-E's style perfectly captured Sophistifunk's essence: taking something ordinary (a baseball cap) and transforming it into something extraordinary through attitude and accessorizing.

When Dr. Dre rapped about still rocking khakis with a cuff and a crease, he wasn't just dropping lyrics – he was codifying Sophistifunk's unwritten rules. When he dropped Let Me Ride and brought in Parliament-Funkadelic's Swing Down Sweet Chariot, it wasn't just a sample - it was a whole movement. Suddenly, George Clinton's mothership had landed in Compton, and the fashion followed. Death Row Records wasn't just a label; it was a whole aesthetic: Versace shirts met platform boots met Timberland energy.

Boyz N The Hood wasn't just showing us LA—it was showing us a whole new fashion language. The Sophistifunk revival took everything we knew about funk fashion and filtered it through a GenX lens. Platform shoes came back, but now they had that 90s DNA. Bright colors returned but with fresh proportions. It was like the P-Funk mothership crashed into a Compton block party and everybody dressed for the occasion.

Snoop Dogg became Sophistifunk's unofficial ambassador, merging high-end Italian fashion with neighborhood authenticity. His appearances weren't just performances; they were fashion manifestos. He could wear Versace silk while discussing Crip history, and somehow it all made perfect sense. This was Sophistifunk in purest form: unapologetically extra while remaining undeniably real.

Sophistifunk aesthetic infiltrated mainstream consciousness through music videos that were essentially three-minute fashion shows. Gin and Juice drove past just being a party anthem—it was a visual clinic on what to wear to a party. Looking cool on the West Coast, wearing a Springfield Indians Jersey, a now defunct minor league hockey team from Western Massachusetts. Plaid Pendleton shirts meant for the Old West of Wyoming looking upscale in South LA, paired with Dickies, elevating urban style without losing soul.

TLC took Sophistifunk to another dimension, mixing baggy overalls with luxury accessories, creating looks simultaneously futuristic and grounded. Left Eye's condom-as-eyewear moment wasn't just provocative—it was Sophistifunk's mission statement: take something functional, make it fabulous, dare anyone to question it.

The Legacy: Why These Movements Matter

Here's what fashion school won't teach: most influential movements aren't planned. They're accidents happening when cultural conditions reach critical mass. Sophistipunk and Sophistifunk weren't trends—they were symptoms of generations that couldn't afford sincerity but couldn't survive without authenticity.

These movements proved fashion could be both intelligent and irreverent, sophisticated and subversive. They showed contradiction wasn't just acceptable—it was essential. In eras where everything became commodified, including rebellion itself, Sophistipunk and Sophistifunk were the last honest lies told.

At SHAO New York, these movements resonate deeply in our design DNA. When Shao Yang crafts collections like 'Class of '98: Rebellion Remastered,' she's channeling that same spirit—the sophisticated rebellion and cultural code-switching that defined Sophistipunk, the audacious blend of luxury and street authenticity that characterized Sophistifunk. This isn't about nostalgia; it's about honoring the authentic blueprint of style evolution that Gen-X perfected: taking cultural contradictions and turning them into something unexpectedly brilliant.

Now, decades later, when kids wear vintage band tees under blazers or platform sneakers with tailored suits, their legacy lives on. Not in museums or fashion archives, but in ongoing dialogues between refinement and rebellion, between inheritance and invention.

True genius of Gen-X fashion movements wasn't in creation—it was in refusal to be canonized. They didn't want to be studied; they wanted to be felt. And if anyone's ever worn something making parents uncomfortable while impressing bosses, they've felt it too.

Sophistipunk and Sophistifunk weren't just fashion movements. They were Gen-X's way of saying two opposing ideas could be held in heads while worn on bodies. They proved intelligence didn't require boredom, rebellion didn't demand destruction, sophistication didn't necessitate selling out. Most importantly, they showed that sometimes the best fashion statements aren't made on runways—they're made in spaces between supposed identities and actual selves.

And that's why fashion history professors will never truly get it. Because Gen-X fashion wasn't meant to be understood—it was meant to be lived.